If technical indicators or oscillators do not drive price, then what does?

Viewing a currency chart, price seems to oscillate in a completely random

fashion, but under the hood what drives price is actually quite orderly. The

spot currency market is a competitive marketplace driven by the economic

model of supply and demand. Many factors influence the equilibrium between

supply and demand, causing shifts in the market price. When more

traders are willing to buy a currency than sell it, the price will move higher,seeking new sellers. The opposite effect occurs when more sellers exist

than buyers: prices fall.

Imbalances in supply and demand may last a few minutes or several

years, depending on the factors that created the imbalance. It is often said

that the currency market is a strong trending market, making it a playground

for long-term trend traders. This can be partially attributed to some

very long-term imbalances in supply and demand created by policymakers,

such as a country’s central bank. Traders who understand how to measure

supply and demand bias are fundamentally better prepared to take trades

that align them with the reason the market is moving price.

In this section we review three measuring tools you can use to gauge

the sentiment of supply and demand.

Measuring Fundamental Strength

Supply and demand for a currency can be affected by the fundamental

strength or weakness of the country it represents. Economic and political

factors combine to encourage participants to buy or sell a given

currency, which affects overall supply and demand. Since currencies are

paired together, it is ideal to determine which country in the currency pair

is stronger than the other and buy that currency while selling the other.

Knowing which currencies are stronger than others requires a systematic

method for measuring the fundamental health of each country involved. In

this section we look at a simple way to measure fundamental strength on a

weekly basis.

Measuring fundamental strength begins by monitoring the health of a

nation’s economy through economic reports. Using the fundamental data

reported on each country, I create a ratio for each country that represents

its overall fundamental strength or weakness. I call this the Currency

Strength or Weakness Ratio, or CSOWR, which I pronounce “sour.” The

CSOWR determines how sour or sweet a nation’s economy is by using data

from economic reports such as the gross domestic product and retail sales

report. If you’re a fan of Chinese food, feel free to call it the sweet-and-sour

ratio. Whatever you call it, the ratio is used to determine which currency

within a currency pair may have the upper hand in fundamental strength.

The weaker a country, the more likely its currency will get beaten up by a

stronger currency in the spot market.

Collecting Fundamental Data The first step in calculating a country’s

sour ratio is collecting the key fundamental data for that country. This

is not intended as a way to trade the news, so it doesn’t need to be done

in real time. The data is released by several government and private institutions,

so visiting each web site would be a time-consuming processI recommend using any one of the good fundamental calendars available

on the Internet to consolidate the data and speed up the process. A list of

fundamental calendars I use to collect data on a weekly basis follows. To

keep the sour ratio uniform across all countries, I collect data using only

fundamental reports available from each country represented by a major

currency. For example, the German Ifo Business Climate data is not used

in the CSOWR because it affects only the euro and no other currency. The

goal of the CSOWR is to compare strength and weakness, apples to apples.

The sour ratio uses data from the following sources:

- Central bank interest rate

- Gross domestic product (GDP)

- Consumer Price Index (inflation)

- Retail sales

- Employment

- Trade balance

These six fundamental reports were also chosen because they reflect

positive and negative measures of the nation’s economy. When any of these

indicators are rising, that is generally thought to be good for the nation’s

currency compared to when they are falling. This ensures that the sour

ratio is truly measuring strength versus weakness and is not skewed by

a report that works against it. An example would be unemployment data,

because a drop in those numbers would be positive for the country but

could reflect weakness in the CSOWR. You could argue that trade balance

data should fall into this category as well, since a falling trade balance

indicates a lower deficit, but that doesn’t necessarily indicate strength in

a consumer-driven economy, because retail sales may fall along with imports.

The choice is up to you. I prefer to calculate the trade balance as

part of the CSOWR.

Simply load the raw number into a spreadsheet for each fundamental

source. You should load each value individually and keep historical data

if you’re interested in doing any kind of trend analysis on a fundamental

value. (We look at calculating the sour ratio and comparing currencies in

the next section.) Finally, if you prefer to use my CSOWRs, I post them

Fundamental Calendars

Provider Web site

- FX Street www.fxstreet.com/fundamental/

- Bloomberg www.bloomberg.com/markets/ecalendar/index.html

- Yahoo! http://biz.yahoo.com/c/e.html

Calculating the CSOWR The CSOWR is a super-secret, complicated

formula that took me nearly 10 years and thousands of hours to perfect.

I’m not really sure why I’m even sharing it with you. Actually, it’s just an

average calculated on the fundamental data that is collected weekly. Keep

in mind that the CSOWR is not meant to be perfect science. It is a cheap,

easy way to measure the fundamental strength versus weakness in a given

currency pair.

To calculate a CSOWR, simply average the values collected from the

fundamental data. Table 3.1 illustrates the data and the CSOWR I calculated

for the Australian economy from January 2009 to September 2009.

Table 3.2 contains the CSOWRs for the United States during the same

time period. You’ll notice a few nuances about the numbers in the spreadsheet.

First, large numbers such as trade balance or employment change

results are recorded in short form. For example, numbers such as 1.45 billion

are recorded as 1.45, and –1,200 is recorded as –1.2. This is done to

keep the spreadsheet easy to read and the CSOWR from being extremely

large. Second, some fundamental reports such as the GDP are not available

monthly. When a report isn’t released in a given month, simply carry

forward the number from the previous release. Third, to predict a CSOWR

before data is released, use the forecast number available on any economic

calendar and then update your spreadsheet once the actual number is

released.

Using the data in Tables 3.1 and 3.2, we can clearly see that the CSOWR

favored the Australian dollar over the U.S. dollar through most of 2009.

Traders can use the CSOWR when contemplating an AUD/USD trade to

determine whether they are positioning themselves on the site of fundamental

strength or weakness. Figure 3.1 illustrates the AUD/USD weekly

chart while the CSOWR favored AUD over USD. Clearly, the fundamental

strength was on the side of the Australian dollar, whereas the United States

slashed its central bank rate, shed jobs and retail sales fell. The CSOWR is

not an indication to trade on its own; you should always consider support

and resistance along with price action before taking any trade. The CSOWR

does provide a quick and easy way to measure fundamental strength between

two currency pairs.

Measuring Institutional Interest

Institutional participants drive massive sums of money into and out of the

spot forex market. Their bias toward a currency should be of interest to

any retail trader because their influence on supply and demand can change

a currency’s value over time. Wouldn’t it be nice to know whether the big

dollars were generally bullish or bearish on a currency before you pulled

the trigger on a trade? Unfortunately, the forex market does not offer

position information on its participants and their positions because there is

no exchange to capture and report the data. The futures market, however,

does offer position information, and there are currency futures traded on

the commodity markets in the United States that can provide useful information

to forex traders.

Every Friday the Commodity Futures Trading Commission publishes

the Commitments of Traders, or COT, report online at www.cftc.gov/

marketreports/commitmentsoftraders/index.htm. The report contains information

on currency futures traded through the exchange, which includes

the euro, Canadian dollar, Swiss franc, New Zealand dollar, and

Australian dollar. Figure 3.2 depicts the COT data for New Zealand dollar

futures from the week of September 22, 2009.

The data on the COT report is captured from the exchange on Tuesday

and published on Friday, rendering it stale the moment it is published.

Although it isn’t real time, the data on the COT report is still useful for measuring

institutional interest in a specific currency. There are many different

strategies developed around the data contained in the COT report, but I use

it only to determine the net positioning of noncommercial traders.Noncommercial traders represent speculators in the futures market.

These are traders who do not intend to take delivery of the futures contracts

they are trading; they are in it for the profit. These are the institutional

traders I’m interested in monitoring because their big dollars help

drive supply and demand forces in the forex market. Without volume and

position information on the spot market, the COT report is the closest thing

a forex trader has to finding out what the big dollars actually think about a

given currency pair. To determine the net position of institutional speculators,

compare the noncommercial short contracts with the noncommercial

long contracts. In Figure 3.2 the noncommercial traders were net long, the

New Zealand dollar futures contracts giving this pair a long bias.

The COT Flip

Monitoring the Commitments of Traders data weekly allows

you to determine the direction institutional traders are headed with

their contracts. For example, if you knew every week that noncommercial

traders were reducing the number of long contracts and increasing the

number of short contracts, it could be a signal that interest is shifting to

the short side. You will also know the precise moment when institutional

investors have switched from being net long to being net short. For trend

traders, the information is especially useful to determine whether the trend

they are trying to trade is with or against the institutional bias for a currency.

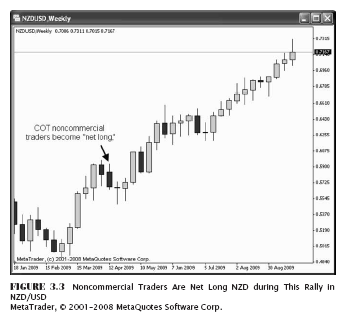

Figure 3.3 demonstrates this point using the NZD/USD weekly chart

between April and September 2009. In April 2009 noncommercial traders

moved from net short to net long, which corresponded with a strong

uptrend beginning in the spot market. At the time of this writing, noncommercial

traders are still net long New Zealand dollar in the futures market.

Just as with the CSOWR, I do not use the COT data as a stand-alone

trading strategy. I use this information to measure institutional sentiment

only. If you are interested in using the COT report to build more advanced

trading strategies, I would recommend reading Sentiment in the Forex

Market: Indicators and Strategies to Profit from Crowd Behavior and

Market Extremes, by Jamie Saettele, part of the John Wiley & Sons Trading

series.

The Influence of Central Banks

Central banks are active participants in the currency market, and their actions

have a direct impact on supply and demand within the marketplace.

It is the role of a central bank to monitor the money supply and make policysending an unclear message to the market through its committee statements

or if the market is unhappy with the decisions being made, demand

for the country’s currency can suffer in the marketplace.

Managing the money supply is an active part of a central bank’s role.

Having too much money in the marketplace can lead to higher levels of inflation

and can stagnate growth. Central banks attempt to promote growth

and fight inflation through a host of economic tools, the most familiar being

interest rates. Using the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank as an example, the central

bank sets two interest rates, known as the discount rate and the federal

funds rate. The discount rate is the interest rate banks are charged to

borrow money directly from the Federal Reserve through a facility known

as the discount window. The federal funds rate is a target interest rate

for banks to charge each other interest for reserve money borrowed on an

overnight basis. When banks have a shortage or oversupply of reserve cash,

they can lend it to each other to cover the reserve requirements at other

banks while making money on the overnight loan. The interest charged on

those loans is set by the federal funds rate. If the Federal Reserve wants to

increase the amount of money in supply, it can lower either the discount

rate or the federal funds rate to encourage lending. Conversely, if the Fed

wants to decrease the money supply, it can increase rates.

You learned in Chapter 1 that open currency positions are paid

or charged an interest premium, depending on their position in the

currency—either long or short. The nightly rollover premium is derived

from the LIBOR, but the overnight rate set by the central bank is the

source for overnight lending, which is ultimately reported to the British

Bankers Association to calculate the LIBOR. The higher the interest rate

set by a central bank is, the higher the LIBOR yield will end up being.

The higher yield creates demand for that currency, and traders often buy

higher-yielding currencies and sell lower-yielding currencies specifically to

collect the interest payments; this is known as a carry trade.

Supply and demand are affected by the demand from carry traders as

more and more traders accumulate large positions over time, ultimately

bidding up the currency. Figure 3.4 illustrates how a high yield from the

Bank of England and a low yield from the Bank of Japan fueled demand

for GBP/JPY for nearly eight years as carry traders continued to hold the

higher-yielding currency. The rally was finally unwound by the global credit

crises of 2008.

The Effect of Fundamental Shocks on Supply

and Demand

Severe imbalances in supply and demand can be created by major world

events or the release of heavily anticipated fundamental data. If the event

decisions affecting a country’s monetary system. If a central bank is

is a complete surprise, traders often favor a safe path of liquidating their positions

and moving to cash until the panic subsides. This reaction to shocking

news or events causes aggressive pressure on supply and demand as

money flows out of one currency and into another. Though dramatic, these

events are often a knee-jerk reaction; the market often returns to its previous

state once traders realize that the sky isn’t actually falling. Bargain

hunters can use these events to their advantage to join existing trends at a

steep discount.

An extreme example happened during the terrorist attacks of September

11, 2001. In the year leading up to the attacks, the dollar had appreciated

nearly $13 against the Japanese yen, rallying from $107 to $120. The

week before September 11, 2001, the USD/JPY was moving lower to test

a support level clearly established on the weekly chart in Figure 3.5. The

shock of the attack is seen as the market fell nearly 400 pips by the end of

trading on September 14, 2001. Even in the face of tremendous global uncertainty,

the principles of supply and demand held up. Two weeks later,

the USD/JPY continued its uptrend as traders decided the U.S. dollar was

the currency to hold.

Fundamental price shocks do not have to be global terror events to

affect supply and demand. Every week the market digests economic data

concerning the health of each nation’s economy, as we discussed earlier

in this section. Occasionally the data the market expects to hear is not

the data it receives. The market often responds with a knee-jerk reaction

to news that doesn’t meet expectations, regardless of whether the data is

positive or negative for the country. These reactions offer an opportunity

to astute bargain hunters.

Figure 3.6 demonstrates an opportunity to trade the AUD/USD after a

price shock has subsided. The Royal Bank of Australia kept its rates unchanged

on July 7, 2009, which is exactly what the market expected. The

initial reaction was a quick rally as short-term traders believed the news

would benefit the Australian dollar. Unfortunately for the bulls, this rally

was only a temporary price shock. The central bank hinted in its rate statement

that interest rates would not begin to rise until obvious signs of inflation

appeared. Following the initial rally, the market continued to sell the

AUD/USD as it was doing prior to the central bank’s statement.

Regardless of the reason for fundamental price shocks, traders should

keep a cool head in the face of vicious, illogical price action. Stay on

the sidelines until it is clear that support and resistance will win out

over panic, then take the trade against those who are still in panic mode.

The fundamental calendar is full of events that could produce trading opportunities

every week. You’ll learn how to trade fundamental shocks in

Chapter 9.

Trading Supply and Demand

Supply and demand may drive price under the hood, but you might wonder

how a trader can take advantage of changes in supply and demand to

make a profit. The battle lines between supply and demand are drawn visually

on our charts as barriers called support and resistance. The terms

support and resistance are synonymous with demand and supply. Support

is seen as buyers increasing demand and pushing prices higher; resistance

is seen as sellers flooding the market with supply and pushing prices lower.

Learning to identify support and resistance by reading price is one of the

most important skills a trader can develop. When you trade along the battle

lines between supply and demand, you have aligned yourself with the real

driving force behind changes in price.

No comments:

Post a Comment